Fire Mountain: Barbra got this beautiful photo of sunset rimming a mountain – possibly 8,200 foot Veniaminof Volcano, its top missing. That’s me left of center, shooting a closer perspective. During our stay at a nearby cabin, the forecast had been for temperatures in the mid 30’s (low single digits Celsius) and the usual 10 to 20 knot breezes. The subfreezing temperatures, heavy sleet and snowfall, and hurricane-force winds we experienced seemed to come out of nowhere.

Every night before we go to bed and every morning upon waking, I slide the dining room/living room window open and scan the lakeshore with a small, powerful spotlight. You never know what you’ll see. Though not necessarily at night, from these very windows we’ve seen brown bears, moose, foxes, owls, weasels, otters, eagles, falcons, beavers, a wolverine and a wolf, not to mention an array of waterfowl including cranes, swans, loons and ducks.

“You oughta take that spotlight and stay in my cabin up on Black,” Fred texted one morning. “You’d like it up there.” Fred’s Chignik Lake home sits atop a high bluff, big picture windows overlooking a good bit of Chignik Lake and the beginning of Chignik River. He spends a fair amount of time doing the same thing we do – scanning for wildlife.

Snow Bunting, Black Lake, Alaska. We’re told that in years past, Snow Buntings were common winter visitors to Chignik Lake. Recently, they’ve been scarce. Although the flock of three birds we came upon only gave me a chance for a couple of quick shots, I was happy to get this record for a project I’m working on to document area birds. (Stay tuned for more on this.) In addition to waterfowl, Black-capped Chickadees, Common Redpolls, magpies, eagles and a Northern Shrike rounded out the avian life we encountered.

Fred’s text came on the last day of December, a few days before Barbra’s winter break was over. The two of us were antsy from days-on-end rain we’d been enduring through most of autumn and early winter. Fred’s offer wouldn’t change the weather, but it would change the scenery. We were in.

That evening we packed up our gear: down sleeping bags, rain gear, extra rain gear for when the first rain gear was soaked, cameras and binoculars, pens and journals, cookware, four days worth of dehydrated backpacking food, four sweet onions and four Fuji apples…

…and awoke the next morning to find that the weather had taken a nasty turn. Rain we can work with, but when winds started blowing spray off the whitecaps on the lake, there was no way Fred would be launching his skiff. “We’ll try again tomorrow,” we agreed. In retrospect, this squall which hadn’t been forecast should have tipped us off that our local weather patterns were unstable.

The following morning we rose early, hoping for the best. During winter, the sun doesn’t break over the mountains rimming our valley till sometime after 10:00 AM, but a flashlight cutting into the pitch black indicated that Fred and his friend Nick were already down at the beach getting the skiff ready. The wind had settled and a mist was falling under a lightless sky that swallowed the lake in inky darkness.

By nine o’clock the first crepuscular twilight silhouetted the mountains to the south. With breakfast behind us and a hint of light on the water, we loaded up the skiff and began the 18-mile run north up the valley. Pockets of near-freezing drizzle appeared and disappeared, prompting us to pull our hoods tight. The forecast – which up here is usually spot on – was for similar weather over the coming days with a few sun breaks mixed in. Ahh, sun breaks. This year, we’ve been living for sun breaks.

As we cut across the lake and proceeded up Black River, a loon and a few mallards and pintails lifted from resting places in coves and a pair of eagles were startled from their riverside perches. Most of the bears are denned up by this time of year, though here and there a few late-run salmon still cling to life in feeder streams. There’s always a chance of seeing a wolf.

Fins, January 2, 2018: The Chignik System is known to receive the latest salmon runs in North America. Still, we were amazed to find a few Coho in a nearby feeder stream near the cabin. More remarkable still, some of these fish appeared to spawning.

A rim of shore ice at the mouth of the stream provided a dining table for otters, who left plenty of salmon scraps for ravens. Although we didn’t see the otters, evidence of their presence was everywhere. We also found signs of moose, foxes, weasels, hares and wolves. In fact, we have reason to suspect that at one point a wolf was just around the bend from us.

After the storm, a fully intact salmon carcass managed to find its way to the shore in front of our cabin – quite possibly plucked from a patch of open water and dropped by this very eagle. I grabbed this shot through a double-paned window – not ideal for a photograph, but what a handsome bird. The moment I opened the cabin door, she took off.

If you come across a single antler from a member of the deer family, it’s been shed, part of an annual process in which male deer, elk and moose grow antlers for the mating season and then lose them. If you come across an entire rack joined by skull bone, it’s the result of a kill. Some years ago, when Fred was scouting out the location for a cabin from his skiff, he came upon five wolves on a downed bull moose right on the beach where he hoped to one day build. Years later, someone found this rack in a nearby alder thicket – undoubtedly that same moose having been dragged there by the predators.

Fred described the cabin he and a couple of friends had built as “sturdy, snug and cozy,” a spot-on description. Insulated from floor to roof and appointed with double-paned windows, the cabin’s 10 x 15 interior is just big enough to comfortably house a diesel heater, three-burner propane stove, hand-made wooden bed frames, small pantry, a table and three hand-made wooden stools. Snug and cozy. The lines looked square and sturdy, points that would soon be tested.

Once Nick got the heater going, the cabin was toasty warm in no time. Fred introduced us to the vagaries of the propane stove, pointed out the water catchment system (a bucket hanging near a roof gutter), and assured us once again that we were welcome to dip into any of the food in the pantry.

I muted the color in this pantry photo. The cabin’s door is never locked and the assortment of canned fish, deviled meat, rice and crackers could be a lifesaver for anyone caught in a sudden storm or out of luck with a dead engine. Although we brought plenty of our own food, I have to confess that the temptation of a skillet of fried Spam was more than I could resist, not having had this treat since childhood. It was, to my mild surprise, every bit as good as I remembered.

With winds pushing 100 miles per hour and sub-freezing temperatures, our water catchment system failed. Fortunately, the wind blew beautifully clear sheets of ice onto our shore.

Following two days of snow and sleet pushed by fierce, cabin-rattling winds, the sun rose serenely over a frozen lake Black Lake. Black River, which leads to Chignik Lake, begins in the gap between the mountains where the light is breaking through. If things didn’t warm up and melt the ice, there was doubt that Fred would be able to make across the lake in his skiff. Fortunately, by the next day the ice had thinned and lay in broken patches. We learned later that two of our neighbors in the village out on a different adventure had to be emergency rescued when the storm came up.

The view from the cabin shoreline after the storm passed: Although we didn’t get the waterfowl and wildlife encounters we’d hope for – and the weather certainly had our full attention for awhile – our four days on Black Lake were wonderfully memorable. And left us with this thought: Why aren’t we doing more landscape photography? New adventures lead to new thoughts, new studies, new goals.

“Hope you guys get lucky and see some wildlife,” Fred said as he and Nick headed to the skiff. Motioning across the bay toward the far shore from where a racket of honking and quacking was issuing, he added, “Of course, those swans and ducks never stop chattering. They’ll keep it up all night.” I helped shove off the skiff, and as the last echoing hum of the boat was enveloped in the valley we’d just come up, we found ourselves wonderfully and utterly alone. Over the next four days, the only human-generated sound we would hear was the drone of a couple of bush planes flying into the village 18 miles to the south.

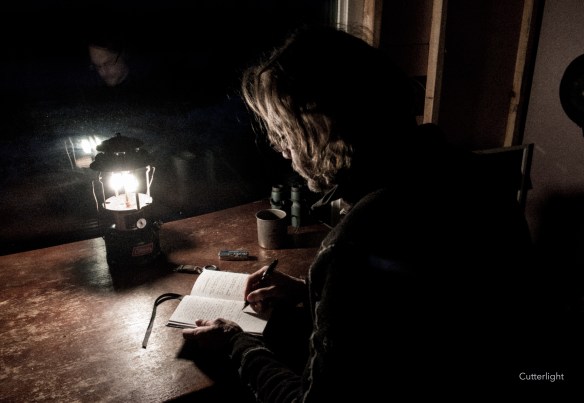

Sketching a novel outline at the cabin on Black Lake: Thirty-some years ago, aboard USS Blue Ridge, a friend and I made elaborate post-enlistment plans to go up into the Colorado Rockies, find a cabin, and live there for a year. We talked about the staples we’d need to lay in: flour, rice, coffee and so forth, the rifles and shotguns we’d take to hunt with, canning equipment, and the desirability of locating ourselves not overly far from a small town where we could reprovision as necessary. We would write. Fundamental to that objective would be pens and journals and a small, carefully selected library of literature. My friend got out a few months before I did… and disappeared. When I called the number he’d given me, his mother picked up the phone. She sounded distraught, with no idea where her son was. No one knew. I’m still not sure if we were kidding ourselves or if we’d really intended to go through with the plan, but either way I couldn’t see going it alone. When an acceptance packet came from the University of Colorado at Boulder, I took the door that was open. But I never completely let go of that idea… someplace quiet, off the grid, armed with books to read and journals to fill.

January 26, Chignik Lake, Alaska