It’s a tough breed of horses that call Mongolia home. Most Mongolians were practically born in the saddle, and even Ulaanbaatar’s urbanites ride them with ease. But these horses are never truly tamed in the western sense of that word. Here a group wades a small salt lake on a mid-October morning a few ticks above freezing.

We woke after spending our first night in a ger to a world of frosted grass and blue skies. After breakfast and some casual rock climbing on nearby outcrops, we piled into the van and resumed our journey south to the Gobi Desert.

Beefy and easy to keep running, four-wheel drive Russian-built vans are standard on the Mongolian steppe.

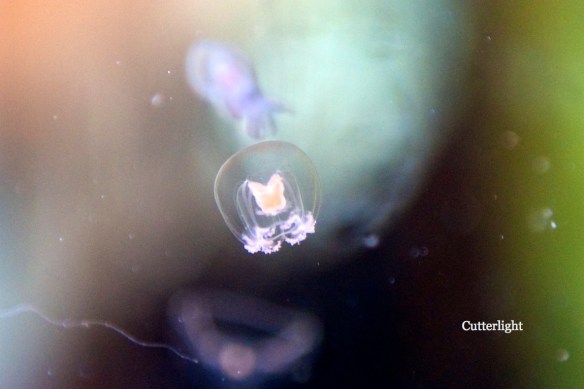

Ruddy shelducks (Tadorna furruginea). The white edge along the lakeshore at the top of this photo is salt. Known for their affinity for brackish water, ruddy shelduck numbers are declining worldwide as salty wetlands are drained for agriculture. In addition to the horses in the photo above, the lake was also populated with common shelducks and teal.

Heads down and tails up, common shelducks (Tadorna tadorna) in muted late fall plumage sift through the lake’s briny muck. Meanwhile, hundreds of passerines, including scores of horned larks, flitted through the air and along the shoreline.

The sun moved higher into the sky. With the soft morning light leaving the lake’s waters, it was time to climb back into the van. The vastness of the land, dotted here and there with horses, cattle, goats, sheep and wild gazelle, continued to mesmerize us. But ever so subtly, we noticed that the grass itself was becoming more sparse.

Off in the distance, a group of especially large-looking horses caught our attention. As we drew closer, humps emerged from their backs. Camels! In less than a morning’s drive, we found ourselves transitioning from the lush grasslands of the steppe to the northern edge of one of the world’s great deserts: the Gobi.

Birch trees tell a tale of water just below the ground’s surface in an otherwise parched landscape, and it was here a band of monks established a monastery long since abandoned and fallen to ruins.

And yet in a sense, the monastery is still alive and vibrant as these nearby ovoos attest. It is the custom in Mongolia to add rocks and other items to these cairns and walk around them clockwise three times out of respect for the sky and earth and to ensure a safe journey.

Brown with late autumn, this familiar grasshopper is a testament to species similarity throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Existing in tremendous numbers in a country where pesticides are still all but unheard of, these hopping protein pills account for the huge number of birds here.

Featuring a dinner of stew with Mongolian-style noodles, goat milk tea, and six liters of wine along with our hosts’ airag (fermented mare’s milk), our second night was celebratory.

That night, we stayed with a nomadic family in their winter camp. Their gers and ungated livestock enclosures (where the otherwise free-ranging animals spend the night) were tucked away from the coming winter wind among rock outcrops.

Nomadic Mongolian herders don’t travel constantly; they maintain two to four seasonal camps. As the seasons change, they pack up their gers, gather their livestock, and take advantage of fresh pasture.

Twice at this camp – once in the evening and once in the morning – we flushed out large coveys of some type of partridge. Both times the birds flew directly into the low sun, so that all we got was the sudden wind-rush thrum of wings, hearts stopped dead in our chests, and winged silhouettes. As usual, rock buntings and other finch-like birds were abundant.

Sunset on another day in the cold, spare paradise we were discovering. Below, the night sky.

Dipper scooping out the horizon… dome of the felt-covered ger glowing white on the sky… Fire inside against the chill of the night… Straight above, the wash of the Milky Way…

Next: The Middle Gobi Desert: Life in a Mongolian ger.

Coming soon: Raptors, Gazelles, Ibex, Picas and a Pit Viper