A female Ring-necked Duck stretches her wings on Chignik Lake. (January 8, 2016)

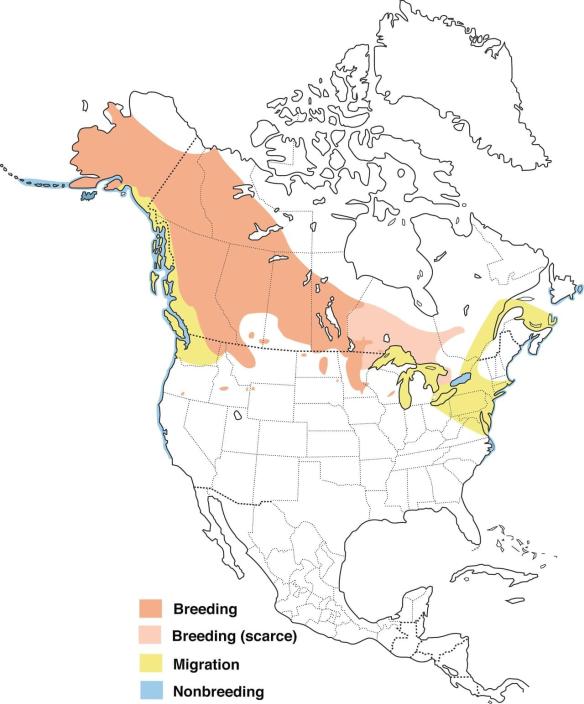

This is a species that may well be expanding its range north. According the several range maps I consulted, including the Birds of the World map below, Ring-neckeds shouldn’t be here with any regularity. It is true that they’re fairly rare on the Alaska Peninsula, but they’re definitely here, and the appearance of pairs in resplendent plumage in late winter and early spring suggests that they’re breeding on the peninsula – or perhaps at points even further north.

The “ringed neck” of the Ring-necked is generally not visible in the field. Apparently it shows better on dead specimens, which were the referents early scientists used when naming this species. Look instead for a distinctively black-tipped bill, a tall head (often showing purple) and a neck that appears rather long compared with most other ducks. In a bit different light, the white ring at the base of this drake’s bill would show plainly, hence one of the alternate local names for this duck, “Ring-billed.” (Chignik Lake, January 7, 2016)

The overall appearance of both male and female Ring-neckeds is similar to male and female scaup. We found that it often paid to carefully glass flocks of scaup when looking for this species. Their bills give them away.

Mousy-gray winter light generally isn’t what I’m hoping for, but here it helps show the distinctive ring at the base of this drake’s bill. Note the peaked head and the scaup-like side.

Although we sometimes saw Ring-neckeds come up from a dive with a billful of aquatic vegetation, it was difficult to determine what they were eating. The weeds, certainly, but very likely whatever invertebrates and small fish that might be mixed in with those weeds as well. Opportunistic feeders, it is reported that Ring-billeds gather in the hundreds of thousands to feed on wild rice in certain Minnesota lakes.

You’ve got to tip your hat to ducks for their hardiness. From front to back: A female Ring-billed, male Ring-billed, and a male Greater Scaup dive for aquatic weeds while ice accumulates on their feathers. (Chignik Lake, January 8, 2016)

This photo offers size comparisons among various ducks: male and female Mallards, male and female Buffleheads, male and female Ring-billeds and a female scaup. (Chignik River, March 14, 2017)

This is a species to watch in terms of range. Maps may look different in the not-too-distant future as conditions on our planet continue to change.

Ring-billed Duck Range Map: with permission from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Birds of the World

Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris

Order: Anseriformes

Family: Anatidae

Aythya: from Ancient Greek, a term used by Aristotle believed to describe a duck or seabird

collaris: from Latin for neck or collar

Status at Chignik Lake, 2016-19: Occasional to Regular late Fall, Wintertime and Spring Visitor, but rarely more than two at any one time. Often in flocks of Scaup.

David Narver, Birds of the Chignik River Drainage, summers 1960-63: Not Reported

Alaska Peninsula and Becharof National Wildlife Refuge Bird List, 2010: Rare in Spring, Summer and Fall; Absent in Winter

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve Bird List: Not Reported

Previous Article: Greater Scaup

Next Article: Tufted Duck – Rare Eurasian Visitor

*For a clickable list of bird species and additional information about this project, click here: Birds of Chignik Lake

© Photographs, images and text by Jack Donachy unless otherwise noted.