Tag Archives: Inupiat

The Bones of Tikigaq: Whaling Festival Site, Point Hope, Alaska

Point Hope, Alaska from the Air

Modern-day Point Hope is located on a narrow peninsula hooking into the Chukchi Sea. In the not-so-distant past, the village was further out on the peninsula, but erosion caused by an encroaching sea has wiped away a good bit of the peninsula, and the old village, called Tikigaq (which means index finger – for the peninsula’s shape), was relocated further inland due to seawater inundation. With evidence of habitation going back at least nine thousand years, Tikigaq Peninsula is regarded as one of the very oldest continuously inhabited sites in North America.

The very essence of an Alaskan bush village is its isolation and remoteness. The only road leading out of Point Hope, Seven Mile Road, ends abruptly a good bit less then seven miles: 250 miles from Barrow, 572 miles to Fairbanks, 694 miles from Anchorage. Thus Point Hope exists as a neatly lain out grid of homes and other buildings surrounded on two sides by water and on one by the vast Arctic tundra. Polar Bears and Arctic Foxes are regular visitors. To experience life in a place so thoroughly separated from the rest of the world is perspective changing – and in an unexpected way, exhilarating.

Large ocean-going barges freight in everything from the school bus – which keeps children safe from both frostbite and Polar Bears – to heavy equipment and building supplies; planes bring in smaller items, including groceries and mail. Hunting and gathering provide a great deal of additional food. This subsistence take includes Bowhead and Beluga whale meat and blubber, caribou, ducks, geese, ptarmigan, salmon, char and grayling along with cloudberries (Rubus chamaemorus) a few blueberries and in some families, seaweeds.

Photographs in coming days will show more of the village and perhaps lend some insight into life there. Thanks for reading.

Ravenous Sea

This camp along the shore of the Chukchi Sea almost looks like an ocean going vessel, the cabin itself the wheelhouse, a flag marking the vessel’s bow as it faces a fall sea. Snow but no ice, you can see how the ravenous ocean eats at the shoreline of tiny Sarichef Island. All this will be gone one day… perhaps in not so many years. October 31, 2010

Photo of the Day: Main Street, Shishmaref, Alaska

To imagine Shishmaref, begin with Sarichef Island where the village is situated. Sarichef is one of several low-lying barrier islands running for about 70 miles along the northwest shore of Alaska’s Seward Peninsula. If you’ve ever been to North Carolina’s Outer Banks, you have some idea of such islands. Sand is everywhere. The above photo depicts a section of the main thoroughfare traversing this village of about 570 residents. There are no roads connecting Shishmaref with the larger world. Vehicles and building materials arrive primarily by ocean barge. Groceries are freighted in by plane. Because of the added freight costs, everything in the small local store is quite expensive. Pink salmon and Dolly Varden Char which migrate along the beach, seals taken from the nearby sea, and Musk Oxen, Caribou, an occasional Moose and waterfowl along with blueberries and Cloudberries taken from the mainland supplement most diets.

In 2010-2011 when we lived there, virtually the entire community was without the kind of city plumbing considered necessary in most of North America. The white plastic container near the middle of the street is where “honey buckets” are emptied into. These containers are then taken to a settling lagoon. Most houses have large water tanks of up to about 300 gallons which must regularly be refilled. The closest village is Wales, population about 145, over 70 roadless miles down the coast.

Photo of The Day: Shishmaref Aerial

Flying into the village of Shishmaref for the first time was an unforgettable thrill. This wintertime photograph, in which the barrier island upon which Shishmaref is located appears to be connected to land, belies the village’s isolation. That is ice, not terra firma, surrounding Sarichef Island which encompasses only 2.8 square miles and rises no higher than 13 feet above the surrounding sea. The village itself is home to fewer than 600 mostly Inupiat residents. Tucked up against the ever encroaching Chukchi Sea, Shishmaref lies a mere 20 miles below the Arctic Circle, 105 miles from the Siberian coastline across the Bering Strait, 601 miles from Anchorage and 2,939 miles from L.A. The wintertime winds, with a fetch of perhaps thousands of miles across frozen northern seas, blew at times with terrifying ferocity and cold, on one memorable occasion all but burying the village in snow.

In the next few photos to come, I will try to show a bit about life in this remote village which is perhaps best known as being on the vanguard of the impacts of climate warming, but where also there is beautifully crafted artwork and a spirit of resilience. As always, your comments are welcome.

November Light: Old Tikigaq and Project Chariot – 160 Hiroshimas in the Arctic

November 29, 12:46 p.m.: Framed below a seal skin umiak whaling boat, the sun edged itself above the southern horizon and lingered for just two hours and 24 minutes. On December 7, the sun will stay below the horizon and remain there for 28 days.

In 1958, under the direction of Edward Teller, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) devised a plan to detonate a series of nuclear devices 160 times the force of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. These bombs were to be exploded just 30 miles southwest of the Inupiat village of Point Hope, Alaska. Teller’s plan – if an action so dangerous and misguided can even be called such – was to blast out a harbor in this far north coastline. The United States government didn’t bother to tell the local residents of this scheme. Nor did they take into consideration that the land in question dId not belong to the United States government; it was and still is sovereign Inupiat territory.

Whale bones mark a sod igloo buried in snow in the ghost town of Old Tikigaq, which was abandoned in the mid 1970’s. Although the sun is only in the sky briefly in November, it is a glorious time of year. This is the November light we have been waiting for.

A caribou hunting party stumbled across AEC engineers and para-military personnel encamped at the mouth of Ogoturuk Creek, near Cape Thompson. That’s when the questions and the lies began.

Grass silhouetted against the southern sky just before dawn, the frozen sea stretching to the horizon near Point Hope, Alaska.

In the end, Teller’s heartless plan was stopped. The bombs were never detonated. The experiment to determine how much radiation local flora, fauna and humans could survive was never carried out.

This is a story of heroes. There was Howard Rock, the co-founder of the Tundra Times, a highly educated, literate Inupiat leader who wrote the first, insistent letters to the United States government demanding that this plan be immediately halted. There were the white scientists from the University of Fairbanks, Pruitt and Viereck, who raised their voices against the project, and in standing up for the Inupiat people and standing against the government were fired by University President, William Wood, who played a less noble role in this story. There were the millions of citizens in the United States and all over the world who were in the streets, protesting nuclear tests of this kind. And there are the people of Point Hope who stood up to the government then and who are still fighting to force the United States government to tell the whole story of Project Chariot.

Because this story is not over.

Over time, as erosion steadily ate away the finger of land jutting into the Chukchi Sea, the old town had to be abandoned. This fall, the entire area was inundated with water when high winds and hurricane force gusts pushed sea water over the rock sea wall protecting the north side of the point.

Although Teller lost his bid to detonate the world’s most destructive arms, in what feels like a tit-for-tat payback, under his direction, in secret, another group of engineers and military personnel were dispatched to the Project Chariot site. This time, they spread radioactive waste on the ground and in the stream. And they buried something there. Something in large, sealed drums.

To this day, the United States government has refused to divulge what was buried.

Since that time, the incidence of cancer has been higher than the national norm among the people of Point Hope. Higher than it should be, even taking into consideration other factors. These are some of the best people we’ve ever had the honor to be associated with. Kind, generous, resourceful, resilient, tough. Their government owes them answers.

Tell-tale tracks leave evidence that an Arctic fox was patrolling Old Tikigaq just before we hiked out. These whale bone jaws located near the airstrip a mile and a half from town welcome visitors to Point Hope. The area around Point Hope is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the Americas – maybe the oldest. While many Inupiat (Eskimo) cultures were nomadic, here the animals came to the people. The point of Point Hope formerly extended far to the west out into the Chukchi sea, bringing the land in close proximity to migratory paths of seals, whales, walruses, char, salmon and other fish. Two impressive capes, Thompson to the south, Lisburne to the north, are home to tens of thousands of sea birds. To the east, Point Hope is situated near the migratory route of thousands of caribou. The sea and the land are the garden that has sustained people here for thousands of years.

For more about Project Chariot, see the book The Firecracker Boys by Dan O’Neill. And although it is difficult to obtain a copy, there is an excellent, 73-minute documentary film titled Project Chariot, copyrighted 2013 NSBSD & Naninaaq Productions: UNCIVILIZED FILMS.

Inupiat (Eskimo) Yo-Yo with Polar Bear Fur

Fashioned from polar bear fur and finished with intricate beading, this Inupiat yo-yo has transcended it’s traditional purpose to become art. Based on a bola design, in olden times tools like this were made of rocks tethered together with sinew and were used to catch birds.

Beautifully crafted by Molly Oktollik, one of the elders here in the village of Point Hope, Alaska, this Inupiat “yo-yo” isn’t what most of us envision when we hear the word yo-yo. In former times, they were made of rocks held fast on sinew tethers and in the right hands were a formidable tool for catching birds. Ptarmigan, for one species, are often easy to get close to, and ducks and sea birds returning to their headland roosts typically fly in on a low trajectory.

These days yo-yos are crafted as pieces of art, or, when less elaborate, as toys. It takes a certain skill, but the two ends can be made to rotate in opposite directions – that is, with one end revolving around the center handle clockwise, and the other revolving counterclockwise. It’s a pretty cool trick if you can get it to work.

Nose Pressed to Glass

Sea ice fascinates us. Our village can be seen in the upper left of this photo. At the time of the photo, north winds had blown much of the ice away from the land. The “sticky ice,” the ice which clings to the shore, can usually be relied on to be safe to walk on. Even this sticky ice is subject to the whim of Mother Nature’s strong winds and current.

Piles of ice form along pressure points of the frozen surface of the sea. There are many histories of boats navigating too late in the season and becoming stranded or crushed between these pressure points.

Recently, wind from the south has closed this lead – the open water to the right. The view from our village today is solid ice as far as the eye can see. The villagers are readying their seal skin boats to go whaling. Soon the bowhead migration will begin. When the north wind blows open a lead, the whaling crews of Tikigaq will patrol the open water in hopes of catching animals that are in their Spring migrations. These whales make up a critical part of the subsistence catch in this Inupiat village.

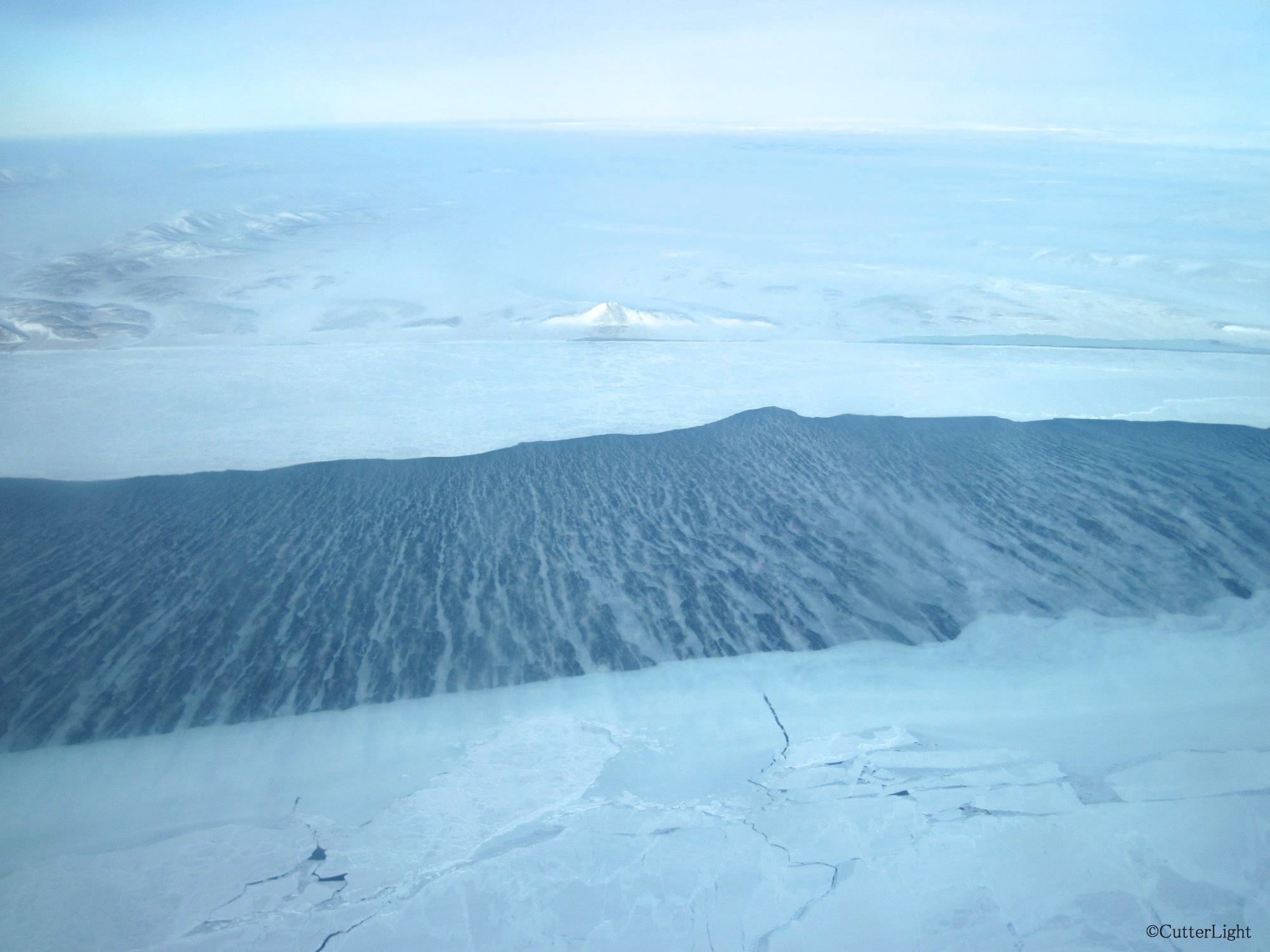

I’ve recently been reading the book The Firecracker Boys. This true story is about a crazy post WWII idea some engineers and scientists had for using a nuclear bomb to blast a harbor between the peak in the center of this photo and the ridge on the left. This is about 25 miles east of Point Hope. The proposed H-bomb was to be 163 times the strength of the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. Scientists and engineers promised to sculpt the land based on human requirements. It was part marketing (using bombs for good) and part wild scientific experimentation. It’s a shocking and crazy true story!

Nose pressed to glass, I peered out from the bush plane window as we lifted straight up, like a helicopter, in the 40 m.p.h. north wind. It seemed scary on the ground. With gusts well above 40 m.p.h., the plane arrived, landed on the airstrip and never turned into the usual parking area. I fought my way toward the plane, slipping along the airstrip as if being pushed down by a strong arm. Once in the plane, I felt calm and safe with skilled bush pilots at the controls.

From the air, the village looks like a patchwork quilt as rooftops peak above a blanket of snow. If the snow and ice were sand, Point Hope could be any beachfront real estate in the world!

Tikigaq School 5th Graders Perform Point Hope Eskimo Dances

The rhythms are played on traditionally-crafted drums; the dances have been passed down from generation to generation. These fifth graders demonstrate that Inupiat traditions are alive and well in Point Hope, Alaska.

With the help of village elder Aaka Irma, my fifth graders and I learned an old Point Hope Eskimo dance that hadn’t been performed in some time. Under the guidance of our Inupiat language teacher, Aana Lane, the students also practiced popular traditional Point Hope dances. The students performed these dances for the Christmas presentation last month to an enthusiastic crowd.

The group of students I have this year is very connected to their culture and heritage, particularly when it comes to dancing. It’s amazing to see every student in the class become so completely engaged in a cultural tradition. During their performance in December, the students captivated the entire audience. The performance culminated with the students inviting one and all to join them on the gym floor in the closing Common Dance – a dance familiar to virtually everyone in our village.