The Tattler of Tattler Creek

All summer and well into fall, we could often see salmon and char from our dining table window as they migrated along the lakeshore beach. The char could be there in any season, following the salmon to gorge on eggs and then making their own spawning run. At other times the char would cruise the lake shoreline chasing down the fry, parr and smolts of Sockeye and Coho Salmon. At that time they would readily come to streamers, and even in winter you could sometimes get a couple of fresh fish for the evening meal.

More interesting than fishing for the char was watching the mergansers and otters go after them. The diving ducks often worked cooperatively, cruising along the shoreline with purpose reminiscent of soldiers on patrol. When they found a school of Dollies they’d herd them against the shoreline or sometimes against ice sheets. The otters behaved in a similar manner, and when there were a lot of char around the otters and the mergansers would set aside some of their natural caution and you could find yourself pretty close to the action if you sat still and waited.

Although it was late in the morning when I took the above photograph, the sun was just barely beginning to emerge over the mountains south-east of the lake. At first it was too dark to shoot, so I positioned myself behind a natural blind of tall, winter-brown grass and waited. There were about half-a-dozen merganser hens, or a hen and her first-year offspring, patrolling the shoreline, catching fish. Then this one came up with the catch of the day just as a flock of Greater Scaup were passing behind her.

So, what do you think? Black and white, or color?

“I’ve been hoping to see you!” Sam came out to intercept me as I was walking along the dirt road past his house on my way to Sitka Spruce Grove. It was an overcast, cold November morning, the tinny smell of snow in the air. “I’ve been seeing a bird I’ve never seen out here. Batman birds. They have a dark head, like Batman’s hood. Nick’s been seeing them too. We’ve been calling them Batman birds.”

“Yeah. I’ve been seeing them too. Just in the last few days, right?”

“Yeah. I’ve never seen them before. What are they?”

“Oregon Juncos. They’re not supposed to be here. I’ve checked my books and range maps on the internet. This might be the first time they’ve ever been out here.”

Sam, in his early 70’s and not more than five-six looked up at me as he rolled the burning cigarette he was holding between his thumb and his first two fingers. For a moment nothing was said. He lifted his arm to take a drag and looked out over the landscape as he let the smoke out. Winter-brown salmonberry breaks and willows, scrub alders an even more drab shade of brown covered the country all the way to the treeline on nearby snow-capped mountains, country that in Sam’s youth had mostly been tundra.

“Things sure are changing here,” he said.

There are still people in denial, people who not so very long ago dismissed Climate Warming as some sort of hoax, who refused to believe any scientists except those who work for the fossil fuel industry. Most of those hardcore deniers have given up the tack of total denial. But they haven’t gone away, and they certainly haven’t conceded their error. Instead, the refrain now is initial agreement, “Yes, it appears the earth is getting warmer,” followed by a deflating return to denialism with, “but the world has always been changing.”

Not with this rapidity it hasn’t – the occasional meteor strike notwithstanding.

The result is that almost anywhere one lives, change can be observed in real time. This might be manifested in new species of flowers and other plants, new birds, other vertebrates, insects… or the rather sudden absence of formerly familiar species. Anyone with a camera has a chance to contribute to real-time, meaningful documentation of the change that is occurring right now all around us.

It’s not just the natural world that is undergoing rapid change. As expanding urbanization follows an overpopulated species across the globe, historic buildings are being torn down, forests leveled, rivers rerouted, lakes and aquifers emptied. Things that had remained much the same for decades, for generations even, are suddenly in a state of upheaval.

Photography is used for many things: to capture holiday moments; family portraits; events of all kinds; and increasingly, to make fine art. But some of the most compelling photographic images have always been and continue to be well-composed, straightforward documentation.

Anyone with a camera can make a meaningful contribution. Get out and shoot.

Fairly new to photography when I got the above capture of a Merlin strafing songbirds at the spruce grove in Chignik Lake, I was somewhat frustrated with my inability to get the bird “tack sharp.” I was shooting with a 200-400 mm telephoto lens at the time, to which I often affixed either a 1.4 mm or 2.0 mm teleconverter, and simply didn’t have the skills to follow North America’s second smallest falcon as it zipped around the grove at breakneck speeds in pursuit of warblers migrating south in late summer. So I climbed a small rise that put me eye level with the upper branches of the trees, chose a section that was well enough lighted, focused on a group of cones, and waited and hoped for the little falcon to enter the scene. The bird obliged, I snapped the shutter, and at least came away with what I would imagine is the only photographic documentation of Falco columbarius in the Chignik Drainage. The species had been documented there… but I think not photographed.

However, before much time passed the photograph began to grow on me. In fact, I actually began to like it. The bird is clear enough to easily identify as a merlin, and I began to appreciate that the blur, while not depicting the bird itself as clearly as I had originally hoped, captures something else: the story of the falcon’s incredible speed and maneuverability as it circled the grove. Had I been able to make a sharp, clean capture of the bird, as I swung the lens to keep up with the falcon the trees would have become a blur. But the Sitka Spruce grove, a copse of 20 trees transplanted from Kodiak Island in the 1950’s when Chignik Lake was first permanently settled, is central to the story here. I love the way the lush green trees draped with new cones anchors this photograph, thereby helping to create a fuller story.

These days, the incredible capabilities of modern lenses paired with technologically advanced cameras have created a push… a demand, actually… for ever sharper images. This has become particularly so in the field of wildlife photography. But it seems to me that sometimes… perhaps often… this insistence on “tack sharp” (and perfectly colored) images of wildlife has come at the expense of the overarching story behind the image.

Over the next several years photographing bears and birds, fish and flowers, landscapes and life at Chignik Lake, as I gradually came to understand more about photography, I returned to the above photograph many times, mulling, contemplating, turning it over in my mind. We already know, in great, tack-sharp detail, what all of North America’s birds and mammals look like. There are thousands of beautiful photographs of just about every species… in some cases perhaps millions of such images. So, how does one employ a camera to go beyond documentation, to tell a larger story? For me, the beginning of the answer to that question started with Spruce Grove Hunter.

We miss our C-dory. A lot. Photographs such as the one above can’t be made without a boat, not to mention the role Gillie played in filling our freezers with tasty halibut, lingcod and rockfish. And for a pleasurable day of leisure, it’s difficult to top fair weather on a calm sea.

While we lived on the Chignik River, we found a shallow-draft welded-aluminum scow to be more practical than the larger fiberglass dory, and so we sold Gillie. Regrets followed. She would be perfect here at our new home on the shores of Prince William Sound. In the peripatetic lives Barbra and I have lived both prior to and during our marriage, with each move we’ve effortlessly let items pass through our lives: beautifully crafted Christmas ornaments, artwork, cherished pieces of furniture, treasured books… even valued fishing tackle. The few items we take pains to keep in our possession mainly come down to cookware, photography gear and fly-fishing equipment. After all, most things are replaceable, and so the metaphor of the bookshelf constitutes an important element of our life philosophy.

The metaphor of the bookshelf is our way of thinking of… things… in a life where we find benefit in living slim and where we appreciate each move as an opportunity to pare down. The idea is to always leave room for the new, and if there is no room, to create it. So rather than fill up shelves with books we’re unlikely to read again, we don’t. Because if your shelves are full, there’s nowhere to add new items to your life – unless you keep adding shelves till your home is crammed full of shelves. It’s lovely to move to a new place and find that you have abundant blank spaces to populate with new treasures. Most things are easy to replace (a first edition copy of A River Runs Through It I allowed to slip through my possession being a noted exception).

Norman Maclean’s classic fly-fishing memoir, Gillie… it’s a short list. Art is replaced by other art. Souvenirs from one place have been let go of to make room for new keepsakes from new places.

We also let go of our aluminum scow when we left the Chignik, and so, taking the optimist’s view and embracing the metaphor of the bookshelf, it appears we now have a space in our life begging to be occupied by a new – or new to us – seaworthy vessel. Something to look forward to.

Known as the Hatan Tuul or Queen Tuul, the Tuul River constitutes a vital greenbelt in Mongolia’s capital city of Ulaanbaatar, and thus an important refuge for a variety of birds. Noticing a couple of sock-like nests in leafless wintertime trees along the river, we set about to find an active nest the following spring. As the above photograph indicates, we were successful, and although shooting into dense foliage in a valley that only received decent light once the sun had cleared the surrounding tall buildings and mountains presented challenges, we managed to get several captures of both male and female White-crowned Penduline Tits. Only about four inches or slightly less in length (8 to 11 cm) and continuously in motion through leafy trees, they made for challenging subjects.

Woven of soft, cottony material from willows and similar trees, we were told that in former times the nests were occasionally used as children’s slippers. In the above photo, the entryway is mostly obscured behind the bird’s torso. Nest-making is primarily the male tit’s responsibility, and although I can’t at the present locate the source, I recall reading that they may make two or even three nests of which only one will be used. What a cozy home for the nesting female and her brood.

I’d been shooting for about four years when I took the above photograph. Still not sure what I wanted to photograph, our Lightroom catalogue was becoming populated with images of wildlife, portraits, landscapes, fishing, food, family events and so forth. But no doubt about it, birds have always held a fascination – and, though I didn’t know it at the time, would become my pathway forward.

It may be that for most of us a general approach is the most logical entry into a new endeavor. But based on my own experiences as well as observations of others, it seems that it is not until we specialize that rapid growth begins. So the angler eventually finds her way into fly-fishing, and not just fly-fishing broadly, but a specific type of fly-fishing. A cook becomes a chef when he undertakes to master a specific culinary repertoire. And so on. The interesting thing is that as one specializes, broader skills and knowledge are acquired and sharpened. So that even catching bluegills or frying an egg is performed with greater proficiency… while simultaneously a leap into a new kind of fishing or cooking, launched for a base of expertise, is also made easier.

A generalized approach feels comfortable, particularly at the start of a journey. The broadness, the lack of pressure to get one thing right, feels safe. But if one truly wishes to master a vocation, it is sound advice to not linger overly long with as a generalist. Specialize. Pick an area and dive deep. Take what is in front of you. Doable. For a couple of years, the best angling available to me was carp fishing. Not my first choice of fish, but I lived within a short bicycle ride of a fine river with a good population of the cyprinids, and so I threw myself into it… and saw my skills in virtually all areas of angling improve. Surely this is the way it is with most things – photography, culinary arts, writing, art… Begin the journey with a broad approach, but with eyes open for a narrowing path.

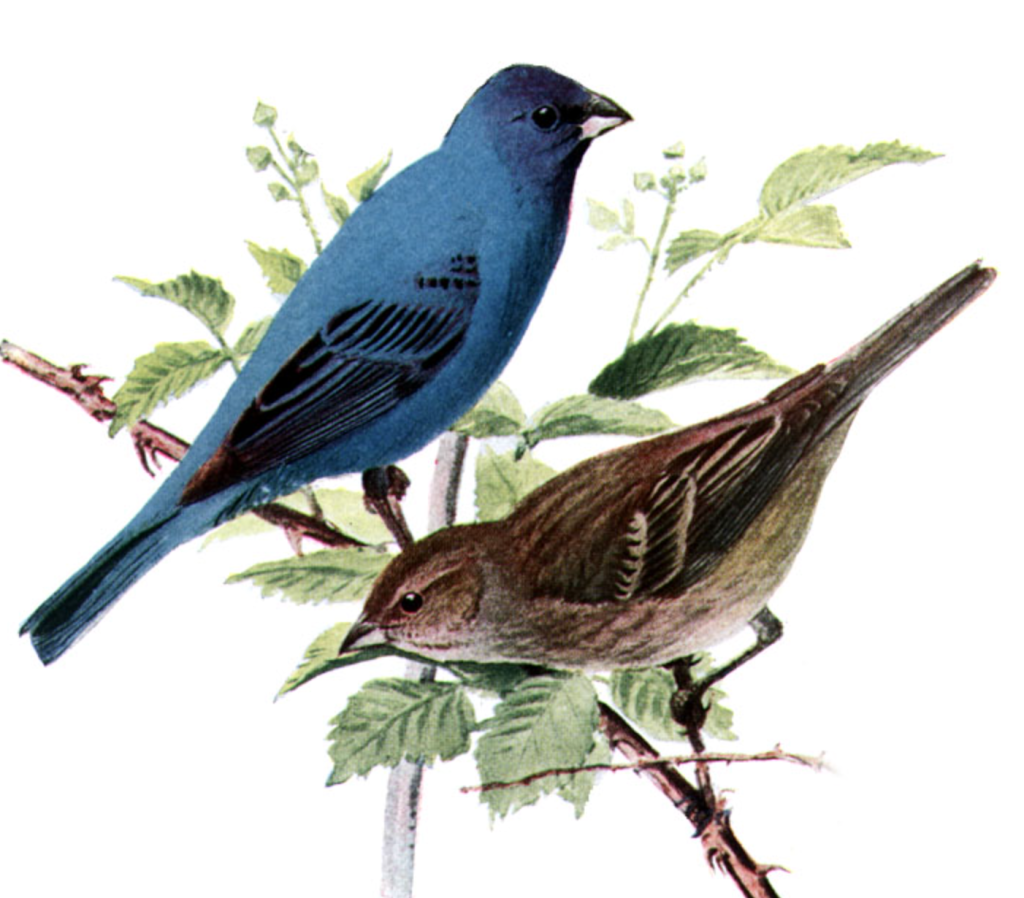

I must’ve been around 13 years old, walking up the Route 322 hill to my summertime job at Martin’s Exxon Plant when I came upon a stunningly bright Indigo Bunting hovering and circling madly back on forth from nearby brush to the shoulder of the road. There on the stony berm, lifeless, was a brown bird of similar size and shape. His mate. The victim of an automobile – most of which, in this man’s opinion, are permitted to travel far too fast for anyone’s safety and sanity… this unending modern obsession with “getting somewhere.” I digress.

It was my first encounter with the deeply rooted connection – emotions – birds can feel for one another. Fearing the frantic male’s behavior would result in him joining his mate as a victim of the traffic whizzing by, I picked her up and placed her in an open area in the brush away from the highway. So that he could mourn more safely.

As years went by I witnessed other examples of similar behavior among various species of birds: crows, magpies, a pair of Narcissus Flycatchers – the one fallen and the one who would not leave his or her mate’s or offspring’s side. A group of Magpies that would not leave an injured member of the flock. A family of Ravens appearing to search for a child that had gone missing.

But the behavior of these Red-billed Choughs was a first for me: not merely a pair of birds bonded through nesting and breeding, but a small flock, gathered on the ground, unwilling to leave a fallen brother or sister. I wish I had thought to make a video record of the event.

On the other side of the rock the chough in the above photograph is perched upon was a jumble of feathers, bony, disembodied feet, blood. The remains of a friend, a loose circle of other choughs pacing solemnly around those remains. I have since wondered what, if anything, the bird in the photo’s perch on the rock, slightly above the others, may have indicated about its status.

I decided to render this as a subtle duotone – a two-colored photograph – by enhancing the red on the one (and only) bill that showed the characteristic coloration of this corvid species. There was very little light when I captured this hand-held image; thus the remaining bills on these otherwise mostly black birds appear in colorless silhouette. Duotones can feel a bit gimmicky, but I like the effect here. What do you think?

I have begun working on a color portrait of one of these fascinating birds and will publish it tomorrow if all goes well.